Longtime Detroiters remember techno festival origins ahead of Movement

The first ever Detroit Electronic Music Festival in 2000 was a grassroots celebration of the city's anything-is-possible spirit.

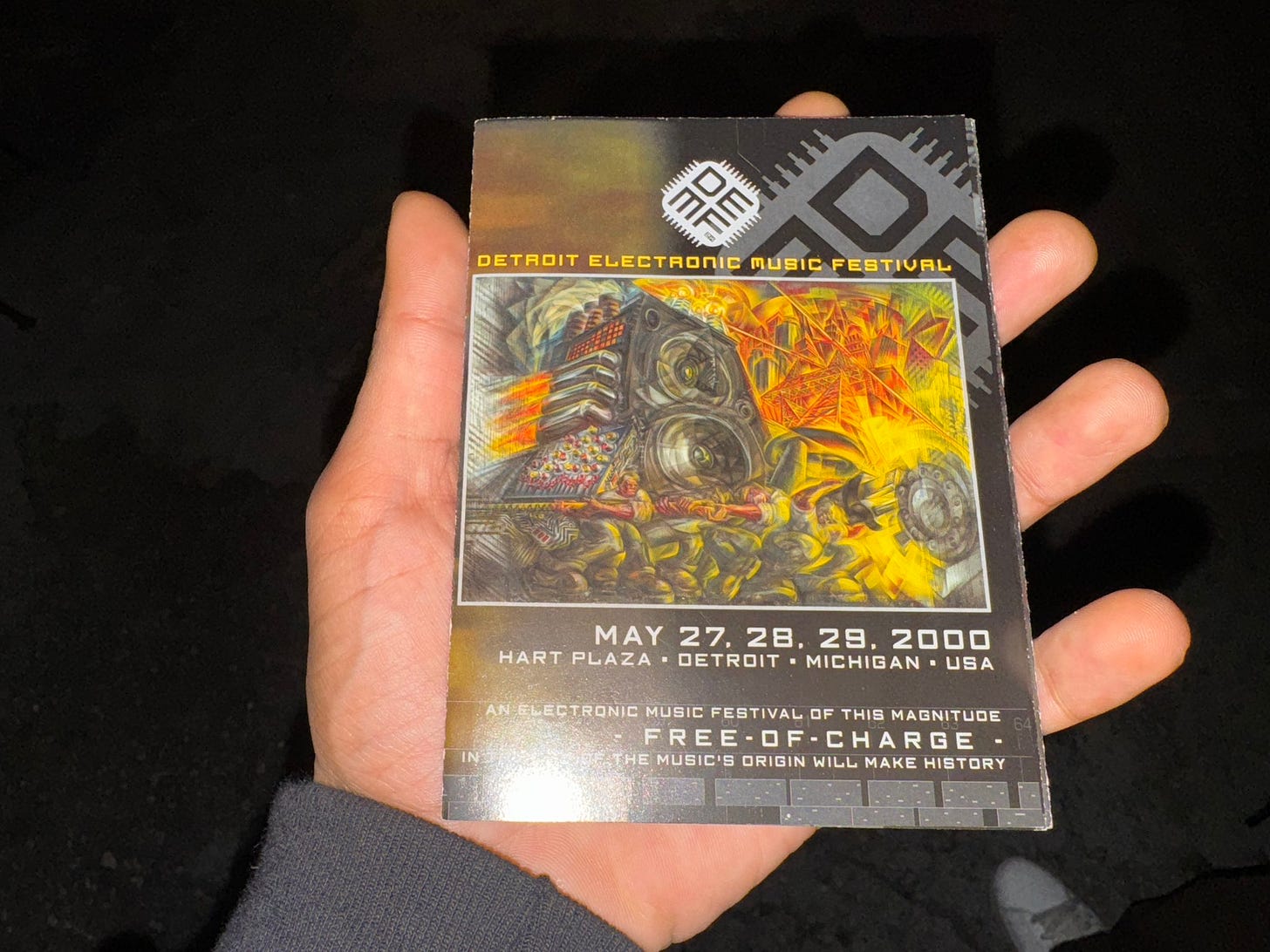

I was stopped by a DJ at Spotlite over the weekend who thought you would appreciate seeing this pamphlet from Movement Festival’s inaugural event.

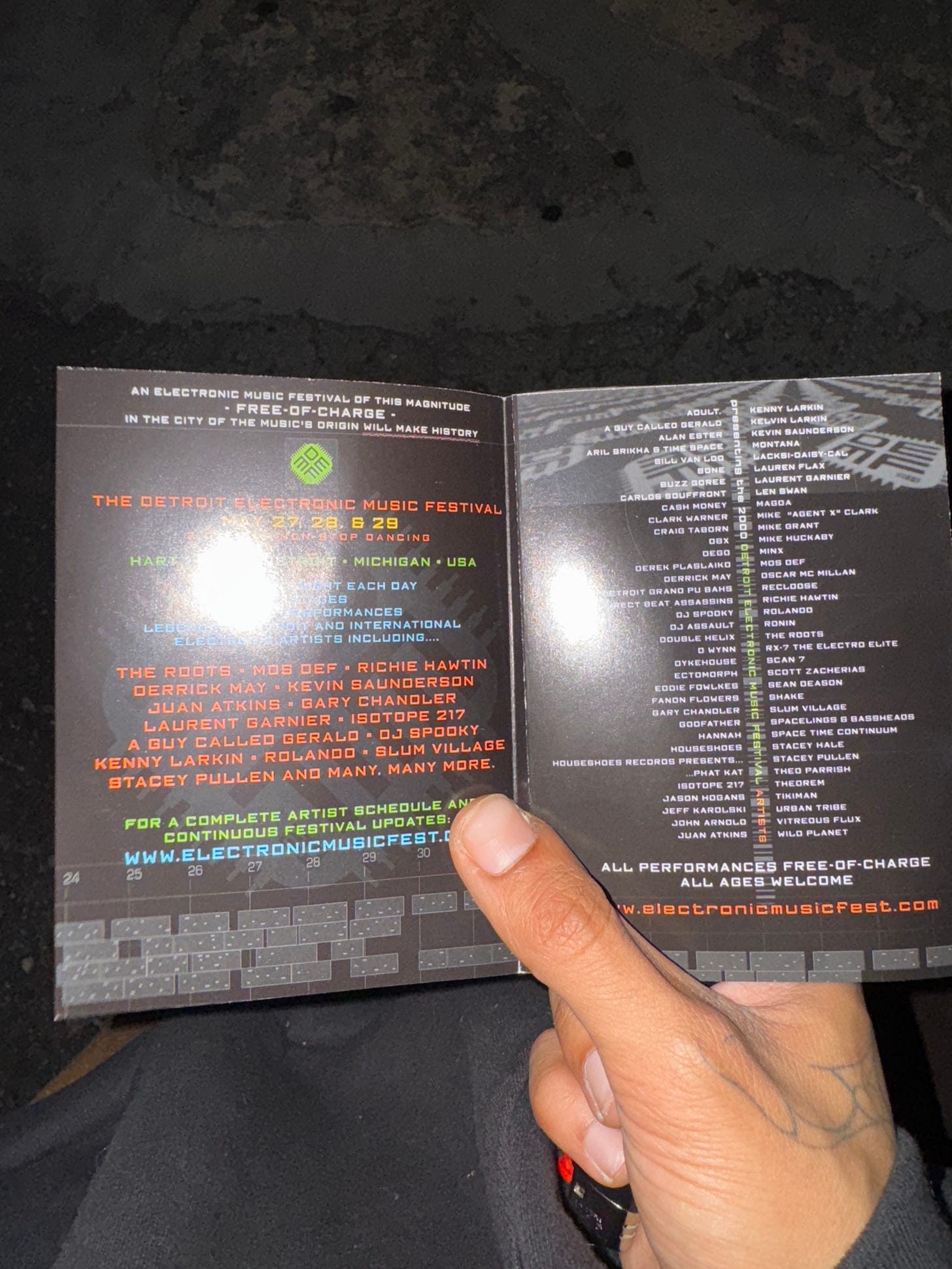

The Detroit Electronic Music Festival featured an impressive lineup, including Derrick May, Kevin Saunderson, Carl Craig, DJ Spooky, Slum Village, The Roots and dozens more. 70 acts in total were on the bill for the festival’s first year.

The first festivals were free, put together without a corporate sponsor and without barricaded containment keeping the public out.

“The inaugural DEMF weathered seat-of-the-pants financing, last-minute marketing and plenty of initial skepticism,” the Free Press’ Brian McCollum writes in this sprawling oral history published Monday.

In it, you can read first hand perspectives from the event’s director of operations, city officials tasked with ensuring public safety, and the DJs like Carl Craig and Derrick May, who performed and helped the festival come together.

The event was an idea that became reality thanks in part to techno pioneer Derrick May, McCollum writes.

“It nearly didn't happen. But on the weekend of May 27, 2000, the scrappy fest blossomed on the riverfront to become a uniquely defining piece of Detroit culture,” penned the paper’s longtime music writer.

Read more in the Free Press: Hart beats: An oral history of the first Detroit Electronic Music Festival

The last few days ahead of this year’s festival over the weekend, I’ve heard from longtime residents who say the festival doesn’t appeal to residents the way it did when it began as the Detroit Electronic Music Festival.

On Wednesday, while getting my hair cut inside the Buhl Building — two blocks from where workers are setting up the festival at Hart Plaza — barber Marcus Iverson told me the event used to completely overwhelmed downtown traffic.

“What they’re doing now with Movement brings way less people down here than those first few years,” Iverson said.

One of the people who watched Detroit techno go global from its infant stages in the late 1980s is Donna Givens-Davidson, my co-host for Authentically Detroit’s Black Democracy Podcast. She spoke about witnessing the first venue open its doors and platform the techno sound that became part of the city’s fabric.

“I grew up with the people who originated Detroit techno, who have gone across the pond and became very famous in other parts of the world. My friend’s husband started the Music Institute downtown on Broadway. That’s where all of the Detroit techno artists used to play in the 80s. He was just 19 when he fixed the place up. No alcohol so they used to drink 40s in the car in the parking lot next door.”

Givens-Davidson says it’s difficult to replicate the energy of those first few festivals under the current economic conditions that prevent many Detroiters from attending.

A 3-day VIP ticket is $449, a general attendance 3-day ticket is $365.

“People spend so much money on concert tickets, I suppose if you’re really into that it makes sense,” Givens-Davidson said. “What I might do is ride my bike along the river walk and listen, just to catch some of it.”

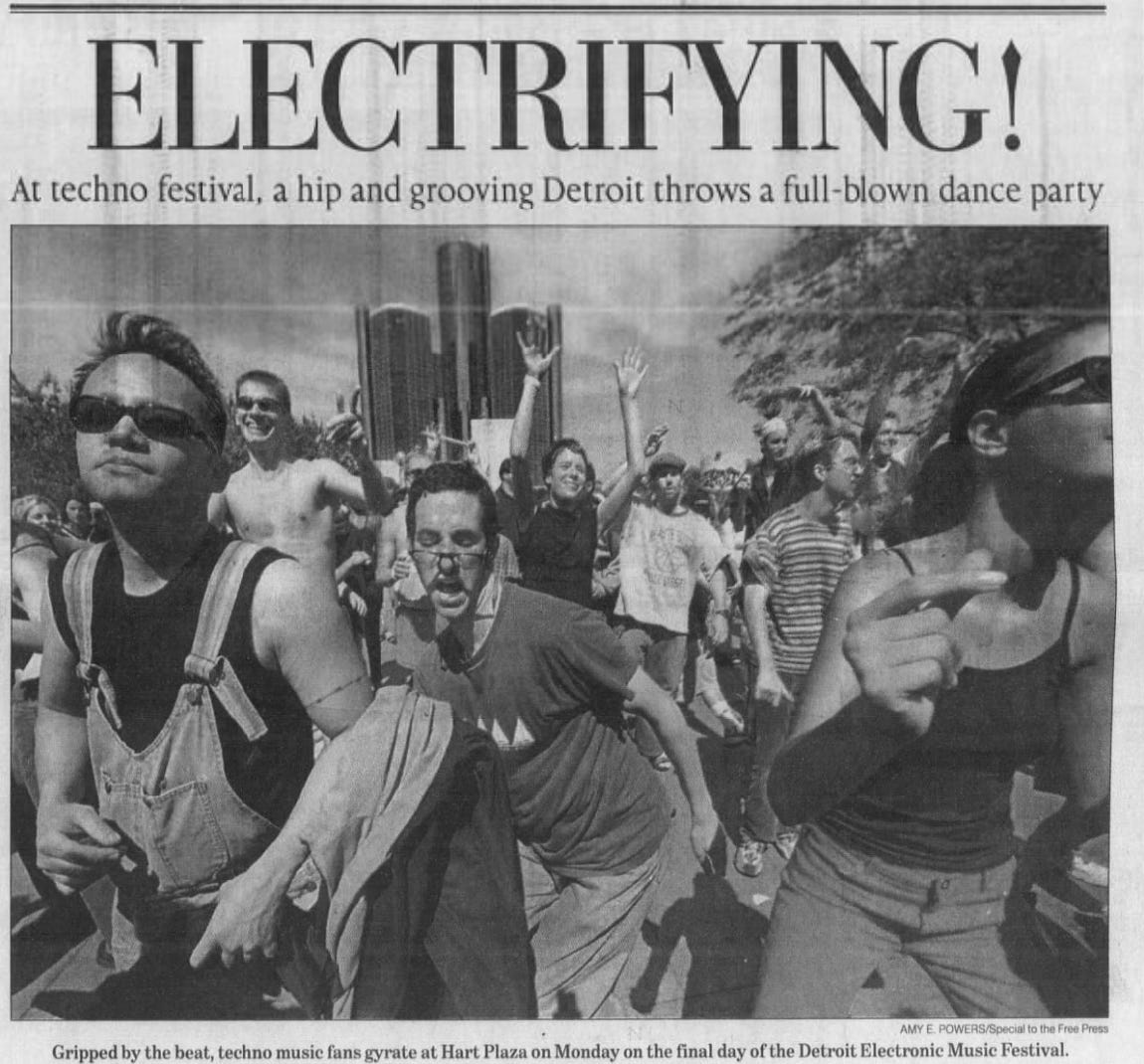

The festivals in 2000 and 2001 reportedly drew more than one million people downtown. It became the most attended event in the 22-year history of Hart Plaza, officials said at the time.

The event was bigger than the Downtown Hoedown, the Detroit Jazz Festival and Freedom Festival fireworks, McCollum wrote.

Hart Plaza remained without barriers blocking off the public, like at those other events. Phil Talbert, the city’s former special events coordinator, told McCollum he had never seen Hart Plaza as crowded as it was during the 2000 festival.

Detroit political consultant Greg Bowens, who in 2000 was a spokesperson for Mayor Dennis Archer told McCollum the first ever festival felt uniquely Detroit.

“I remember the feeling of celebrating something uniquely Detroit and the opportunity DEMF represented — visitors, press and business from across the globe coming to the D,” Bowens said. “This was bigger than the international Grand Prix in the sense that regular folks, Detroit folks, wouldn't just be sitting in a grandstand next to a racing fan from Italy watching cars zip by. We were in a totally immersive, musical experience, dancing with people from around the world at a giant free party.”